When I Told My Mother, I Didn't Want Her to be Alone

I saw a brochure on how to tell the children that you have cancer, but nothing about how to tell your mother.

Telling my kids required carefully thinking it through and staying calm. Telling my mother necessitated that and more.

Ronni's mother, Lynne Gordon, in her garden.

My sister and I were like directors of a production. The “actors” had to be in the right spot at the right time, at the moment when I called on the phone.

The players were my aunt and uncle, the doctor across the hall from my mother’s apartment, all New Yorkers, and my sister, long distance from Boston.

My father – her husband of 55 years – had died the year before. She was still grieving the loss of a beautiful marriage, and I didn’t want her to be alone.

"Not my baby."

My aunt and uncle came over on that spring day in 2003. I called and told Mom that I had acute myeloid leukemia and would be treated at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. She could move in with my sister and brother-in-law, who lived nearby, so that she could visit me daily when I was hospitalized for chemotherapy. Then our doctor friend came over to answer questions that she might have. My sister called up afterwards.

She sounded calm on the phone, but later she would tell me that she cried and said, “Not my baby.”

After the chemotherapy started, it must have been terrible to see me suffer with fevers up to 105 degrees, and with diarrhea, vomiting, chills so intense that the bed shook, and mouth sores so painful that I couldn’t eat.

Rising to the occasion

But she rose to the occasion. She made friends with the nurses, and when they did their “platelet dance,” flapping their arms so that the platelet infusions would give my low counts a boost, she flapped along with them.

We walked to one of the hospital entrances – me often dragging an IV pole – and sat outside in wheelchairs. We drank a Coke. The U-shaped driveway was decorated with plants and bushes. My mother called it The Riviera.

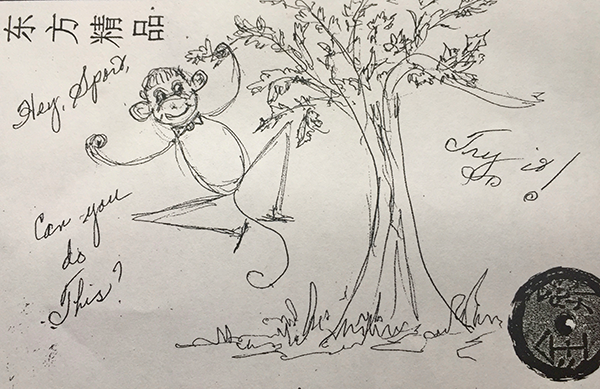

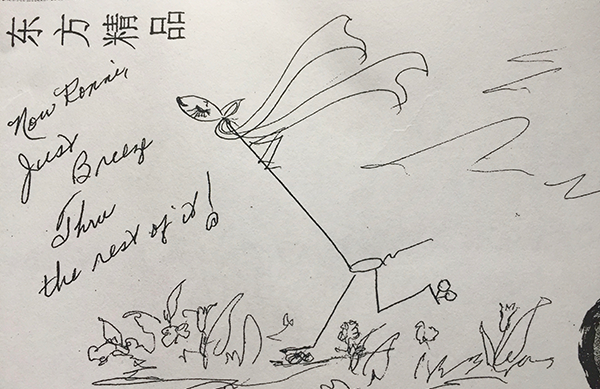

She drew cartoon characters on the board in my room. A monkey swung from a tree. The caption read, “Hey, Ronni, what do you say, chemo’s going to be done today.”

Cartoons drawn by Ronni's mother.

In between sessions, she came home with me. We took short walks, had decaf at my kitchen table. She laughed with the kids.

"The patient is OK, but the mother isn't."

One night when I had gotten dehydrated, I fainted onto the bathroom floor. She caught me in her arms. She rode up front in the ambulance that took me to the local hospital.

Because my blood counts were so low, I waited in isolation for a bed to open up in Boston. She inquired constantly at the desk. The nurse at the other end must have asked how I was. I heard the nurse in Springfield answer, “The patient is OK, but the mother isn’t.”

Once we got to Boston, she calmed down, knowing I was in the best hands.

After my stem cell transplant some six months later, when it was time for her to go back to New York for good, we were glad for the time we had together. We even said that in an odd way, we had had fun. You wouldn’t choose leukemia for a distraction after your spouse’s death, but it helped her over the hump.

Join the conversation